Interview with Author Charles Ray

August 25, 2021

Today, we have an interview with Charles Ray. Charles has been writing fiction since his teens, and actually won a national short story writing contest sponsored by his Sunday school magazine. He has done articles, cartoons, reviews, and photography for a number of publications in Asia, Africa, and America. He writes in several genres: mystery, fantasy, urban fantasy, and humor, in addition to non-fiction. His favorite happens to be mystery. Charles is a very experienced author and has a lot to say about his work, so without further delay we present, an interview with Charles Ray.

Where did you get the idea for your characters? Was it based on any personal experience?

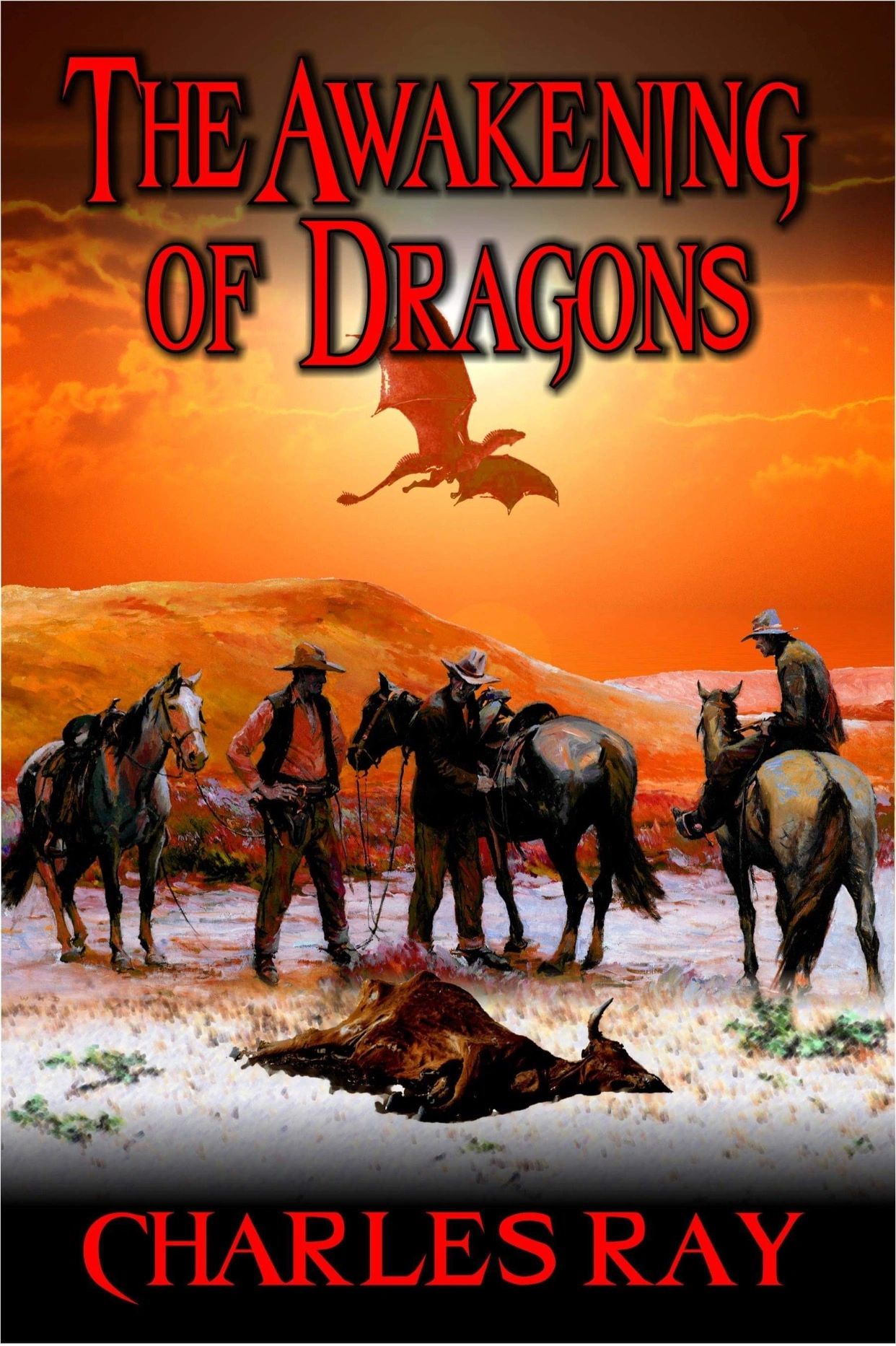

I had this idea for a story about a samurai who came to America and got involved in adventures with a cowboy. When I was asked to do a Western horror story, after running a number of plots through my mind, I had this epiphany. What if there was an isolated area—like the Dakota badlands—where a few dinosaurs had survived but were cut off from civilization, but an earthquake or some other natural disaster removed the barriers? Then, I thought, who would be most capable of dealing with these monsters? Well, what about a samurai who comes from a culture that believes in dragons? It wasn’t based on personal experience, but as how many of my characters and plots get started – I sit somewhere in a corner and start asking myself, what if(?) and then take the craziest question that comes to mind and start writing.

What got you interested in becoming an author?

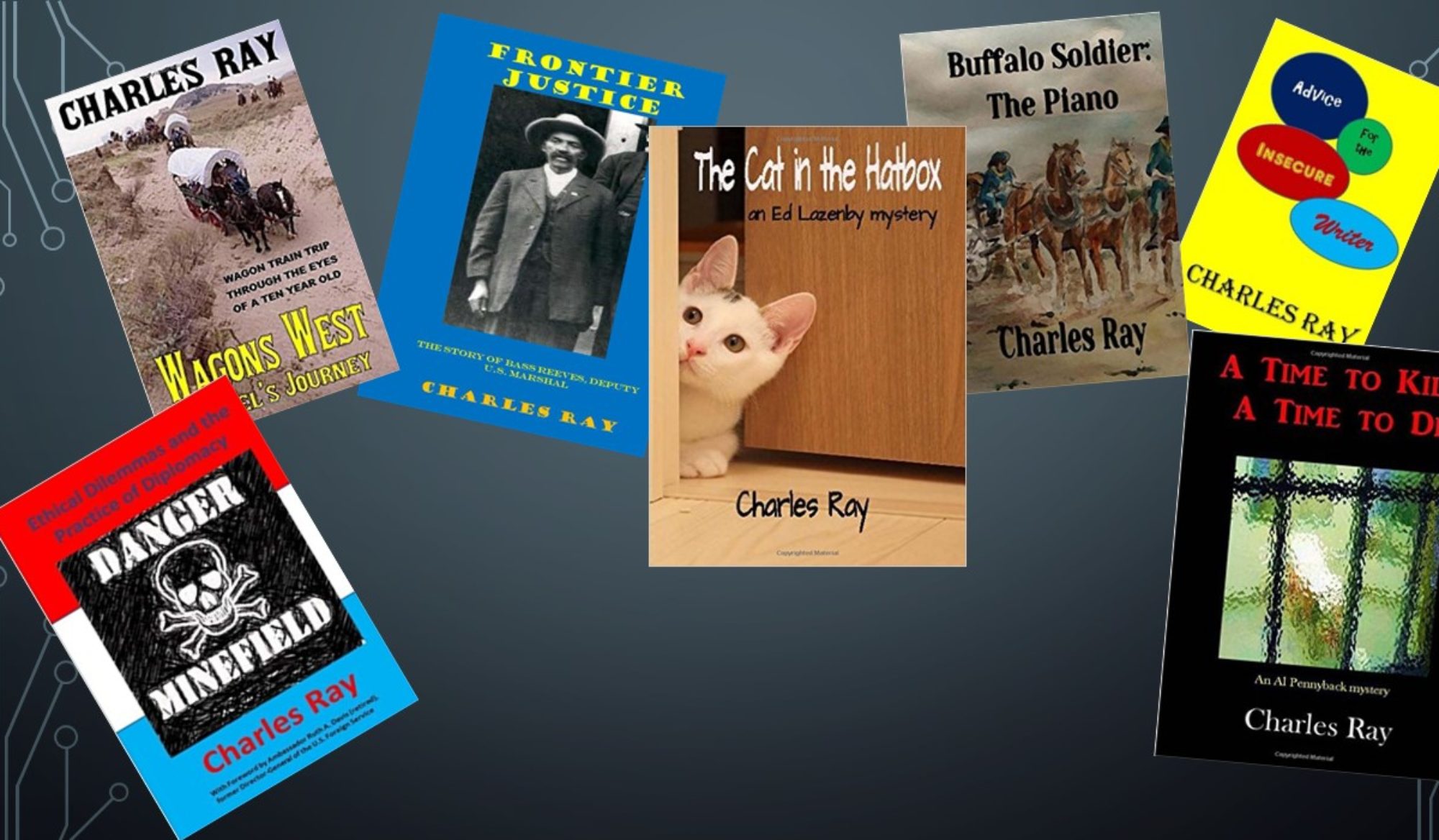

When I was young, I was something of a recluse. I preferred books to dealing with people and spent a lot of time making up stories. When I was twelve or thirteen, my English teacher talked me into entering a Sunday school magazine short story contest, and my story won first place. Ever since, I’ve aspired to be an author. For years, from the early 1960s until 2008, I wrote newspaper and magazine articles, and the occasional poem for publication. My first book, which wasn’t even fiction, was published in 2008. I published my first fiction, a mystery, in 2010, independently because of the bad experience I had had with the publisher of my first two nonfiction books. I began branching out shortly afterwards and have done urban fantasy, traditional fantasy, and children’s books. I did some historical fiction that because of the period also qualified as Westerns, which led to doing a series on the Buffalo Soldiers and a series of books about Bass Reeves, one of the first African-American deputy U.S. marshals west of the Mississippi. That eventually became a focus on writing Westerns. I was, as I said before, asked to write a Western horror story, and since I had not done horror before took it on as a challenge.

When you start writing your story, do you plan to write it into a series of books or did you want to write just one?

Sometimes when I start a book I have it in mind to do a series, as was the case with my Caleb Johnson Mountain Man series. At other times, I only have the single story in mind. When I started ‘The Awakening of Dragons,’ that was the case, but as I neared the end, I saw the potential for at least one or two more stories with the same main character, so I ended it on a kind of cliff hanger. Not the unresolved issue kind of cliff hanger, but the kind where something happens that makes a reader wonder if there’s more to come.

What is the best cure for writer’s block?

Writing every day, even if it’s just impressions of the weather or making journal entries, is the way I avoid writer’s block. Another is to have more than one writing project going at a time. That way, when you’re having trouble coming up with that next bit of dialogue or narrative, or you can’t figure out what to do about a certain plot twist, you can move to a fresh story and work on it for a while. I find this often helps me get past problems with a story. The main thing, though, is to write, write, and write some more.

What do you do to pass the time when you’re not writing? Do these hobbies influence your writing in any way?

I have a full menu of things to do. I spend time with my grandchildren, who also provide me inspiration for some of my stories or for the weekly column I write for a newspaper in the Philippines. I keep a camera with me wherever I go, and take tons of photos, some of which I have used in my nonfiction books, and I like painting and drawing. I was once an editorial cartoonist for a newspaper in North Carolina and did covers and cartoons for magazines in the 1970s. Both photography and art give me ideas for stories. For example, I love photographing butterflies and the sight of two butterflies fighting in midair gave me the idea for a couple of stories I’ve done. Nature photography is my favorite and is the inspiration for a short story I’m currently writing for a special volume planned soon where I merge a love of nature with the life of a mountain man to try and show what motivates a person to become a mountain man in the first place.

Do you ever get tired of writing in the same genre?

Since I don’t write in just one genre, that problem never arises. I only write in the genres that I read, too. For example, I tried reading a romance novel once and couldn’t get past the third page, so I have never even tried to write in that genre.

Would you ever be opposed to turning one of your books into a movie if a studio were to ask you?

Are you kidding? I would love to have not just one, but some of my books turned into movies. That way I could reach an even bigger audience.

Do you mix any commentary about the world into your books, like the state of the world, commentary on capitalism, politics, etc.?

Not explicitly. I do have a thing about bullying, and many of my books will include a bully who gets his comeuppance, but I never lecture; I just show the bullying, show people getting tired of it and how they deal with it. I figure that people who hate bullies as much as I do will get the message and any bullies who accidentally happen to pick up that particular book will pretty quickly stop reading. I do try to show a diversity in characters—gender, ethnicity, and the like—and show how a wide variety of people have played a part in history, but again I never preach or lecture. I try to be historically accurate, but do not let that stand in the way of telling a good story. As an example, I once wrote a story about a ten-year-old and his family moving west. It wasn’t a bestseller but did enjoy modest sales. One reviewer, though, hated it because she didn’t think a ten-year-old could do some of the things I had my main character doing. The problem with her thinking was she was basing it on what kids can do today, rather than a time when you had to take on adult responsibilities early in life.

If you were to leave any of your novels open-ended, do you like hearing fan feedback on what they think either the ending means or what happened after the ending? Or would you prefer they just take the story as it is?

Other than leaving teasers at the end of the mysteries, and now the horror novels, I don’t really leave stories open-ended. Having said that, I have no objections to a fan giving me ideas for what happens next. I once did a short story based on a prompt and posted it on a short story site. A few readers expressed dismay that I had killed my main character at the end of the story and one pleaded with me to figure a way to resurrect him. As it turned out, I had ended the story with a shotgun blast through a door behind which the character was standing, so it was an easy matter to have the door absorb most of the pellets and him just getting a few just under the skin. Painful but not fatal. That resulted in a series of ten short stories that were the most widely read on that site until it went out of business. I don’t do too many short stories anymore, except for the occasional anthology. They’re much harder to write than a novel, but when it’s done right can be quite satisfying.

What’s next for you? Do you have a new book in the works or any other projects you’d like people to know of and get excited about?

I plan to do a few more Western horrors, have, in fact, already written a second—different character and plot—and I’m concentrating on my two most popular characters for a while. I wrapped up two series, at least for a while. Last year I did a mystery with a new private detective, a young version of a long-running series and a kind of follow-on that served to wrap up the original series. I’m toying with the idea of doing a few more with this new character and seeing where it goes. Other than that, for the next year at least, I will be focusing on expanding my popular characters.

I would like to thank Charles for taking the time to conduct this interview. We greatly appreciate the time taken out of his busy schedule talk with us and we hope that this was an interesting look into one of our many esteemed authors. Thank you for reading, and thank you again, Charles, for doing this interview.

After a not-so amicable divorce from the ‘publisher’ who’d issued my first two books, and the decision to immerse myself in the waters of independent publishing (which entailed learning layout and design and a few other skills), I began to crank books out in earnest. I started with a mystery series featuring a retired army special ops guy working as a PI in Washington, DC, soon added a western series about the famed Buffalo Soldiers of the US Ninth Cavalry, while still doing blogging and a little copywriting and content generation on the side. To my surprise, while they didn’t make any bestseller lists, my books actually began to sell—be bought—and reviews indicated people were reading and responding to them. Sometimes those responses were negative, but I learned from those negative reviews, and I think the books got better. Hell, I know they got better; I went from selling two to three copies a month to fifty or more, and some months I even managed to sell as many as 800 copies of one of my e-book versions. I even have a couple of books that are what I call my perennial sellers. My book on Bass Reeves, the first African-American appointed a deputy US marshal west of the Mississippi, which has been out for three years now, averages 10 to 15 e-book and 4 to 10 paperback sales per month, even now. That’s nothing to brag about, but with more than 20 books doing that now, it is significant. Last year (2016) my net income from book royalties passed the $7,000 mark. That doesn’t put me in the Fortune 500, not even the Fortune 500,000, but for an indie author, that’s nothing to sneeze at.

After a not-so amicable divorce from the ‘publisher’ who’d issued my first two books, and the decision to immerse myself in the waters of independent publishing (which entailed learning layout and design and a few other skills), I began to crank books out in earnest. I started with a mystery series featuring a retired army special ops guy working as a PI in Washington, DC, soon added a western series about the famed Buffalo Soldiers of the US Ninth Cavalry, while still doing blogging and a little copywriting and content generation on the side. To my surprise, while they didn’t make any bestseller lists, my books actually began to sell—be bought—and reviews indicated people were reading and responding to them. Sometimes those responses were negative, but I learned from those negative reviews, and I think the books got better. Hell, I know they got better; I went from selling two to three copies a month to fifty or more, and some months I even managed to sell as many as 800 copies of one of my e-book versions. I even have a couple of books that are what I call my perennial sellers. My book on Bass Reeves, the first African-American appointed a deputy US marshal west of the Mississippi, which has been out for three years now, averages 10 to 15 e-book and 4 to 10 paperback sales per month, even now. That’s nothing to brag about, but with more than 20 books doing that now, it is significant. Last year (2016) my net income from book royalties passed the $7,000 mark. That doesn’t put me in the Fortune 500, not even the Fortune 500,000, but for an indie author, that’s nothing to sneeze at. thought about it, in fact, until my editor friend asked her question. But, that’s the answer to how I’ve done over 60 books in 11 years. The thing is, I wasn’t even counting them as I was cranking them out, and didn’t even notice it until a few years ago, a friend who was introducing me to speak at an event, mentioned that I’d writing a sh-tload of books. I still don’t stop to count them often, but every now and then, someone will mention it, and I’ll count. It keeps going up. I don’t have a target, maybe to have at least one book for each year of my life—no, I know, to have more than 100. That’s nice, round number, don’t you think.

thought about it, in fact, until my editor friend asked her question. But, that’s the answer to how I’ve done over 60 books in 11 years. The thing is, I wasn’t even counting them as I was cranking them out, and didn’t even notice it until a few years ago, a friend who was introducing me to speak at an event, mentioned that I’d writing a sh-tload of books. I still don’t stop to count them often, but every now and then, someone will mention it, and I’ll count. It keeps going up. I don’t have a target, maybe to have at least one book for each year of my life—no, I know, to have more than 100. That’s nice, round number, don’t you think.