I currently have over 60 published books—probably close to 70 right now, but I’m too busy to count them—and an editor friend of mine asked me how on earth I found the time to write so many. An interesting question, that; one I hadn’t given much thought to. Too busy writing, don’t you know.

But, it was a fair question, and I took a stab at answering her. As I was typing the email, recounting for her my writing process, a realization hit me—I’m something of an obsessive-compulsive, schizophrenic, anal-retentive, driven person; or, so would the writing routine I’ve been following for almost as long as I can remember seem to indicate. In the following paragraphs, I will outline it for you, and let you decide if I’m engaging in hyperbole or not.

First, a little background is in order. From the time I was 17, until I retired from the US diplomatic service in 2012, I was a government employee (20 years in uniform, but that’s also government employment). That meant, I moved frequently, had odd hours, and, while some of my work was exciting, I was mostly involved in repetitive, bureaucratic tasks.

During those years in government, I wrote. And, by this I mean, I wrote for publication. While I was in the army, I moonlighted on several occasions as a reporter for local newspapers—the only restriction was that I couldn’t write about things on the base where I was stationed. I also did freelance stuff for regional and national magazines. Now, this is called moonlighting, because you have to do it during non-duty hours. So, I pulled a lot of late-nighters, which isn’t a big problem, because for as long as I can remember I’ve only slept an average of 6 hours per night anyway. When I retired from the army and joined the US Foreign Service, I could no longer work directly for civilian publications, but I did continue freelancing, and again, I wrote early in the morning before going to work, and late at night after returning from work—seven days a week, holidays included.

Then, in 2006, I decided to take a serious stab at writing something longer than a newspaper or magazine article. I’d been secretly scribbling a couple of novels on occasion, thinking that I’d like to actually write a book, but hadn’t quite built up the nerve to finish one. A young man who worked for me when I was ambassador to Cambodia (2002-2005) suggested that I compile my leadership techniques into a book because, though they were a bit odd, they were effective. There was another thing added to my after (and before) work hours routine; scribbling out the chapters of that damned book, which took me two years. I finally got it finished and published in 2008. That was a traumatic experience, one that I’ll not repeat in this lifetime—but, that’s another story—but, it demonstrated to me that I could, in fact, write books in my spare(?) time.

So, from that point, I began to seriously engage in writing, making it a point to write at least an hour every morning before going off to work, and another hour or two in the evening before falling into bed. On weekends, when there was no official function, or the wife and I weren’t traveling, I wrote at least three or four hours.

I’d never given it much thought before, but I soon discovered that when you do this, and, like me, you’re a fairly competent and proficient typist (I do 60 WPM), you can crank out a lot of words each month, and I mean a lot. I had a target of 1,000 to 2,000 words a day, something an old country editor in North Carolina taught me back in the 1970s as good exercise for the writing muscles. Now, if you do the math, in a 30-day month, that amounts to 30,000 to 60,000 words—a novelette or a medium-length novel, and in one month. Of course, if you factor in proofreading and all the other stuff you have to do, it would take longer than a month, but, on the other hand, when you look at four weekend days per month with an opportunity to crank out 6 to 8,000 words, you can do it in even less. Once I discovered this, I was off to the races.

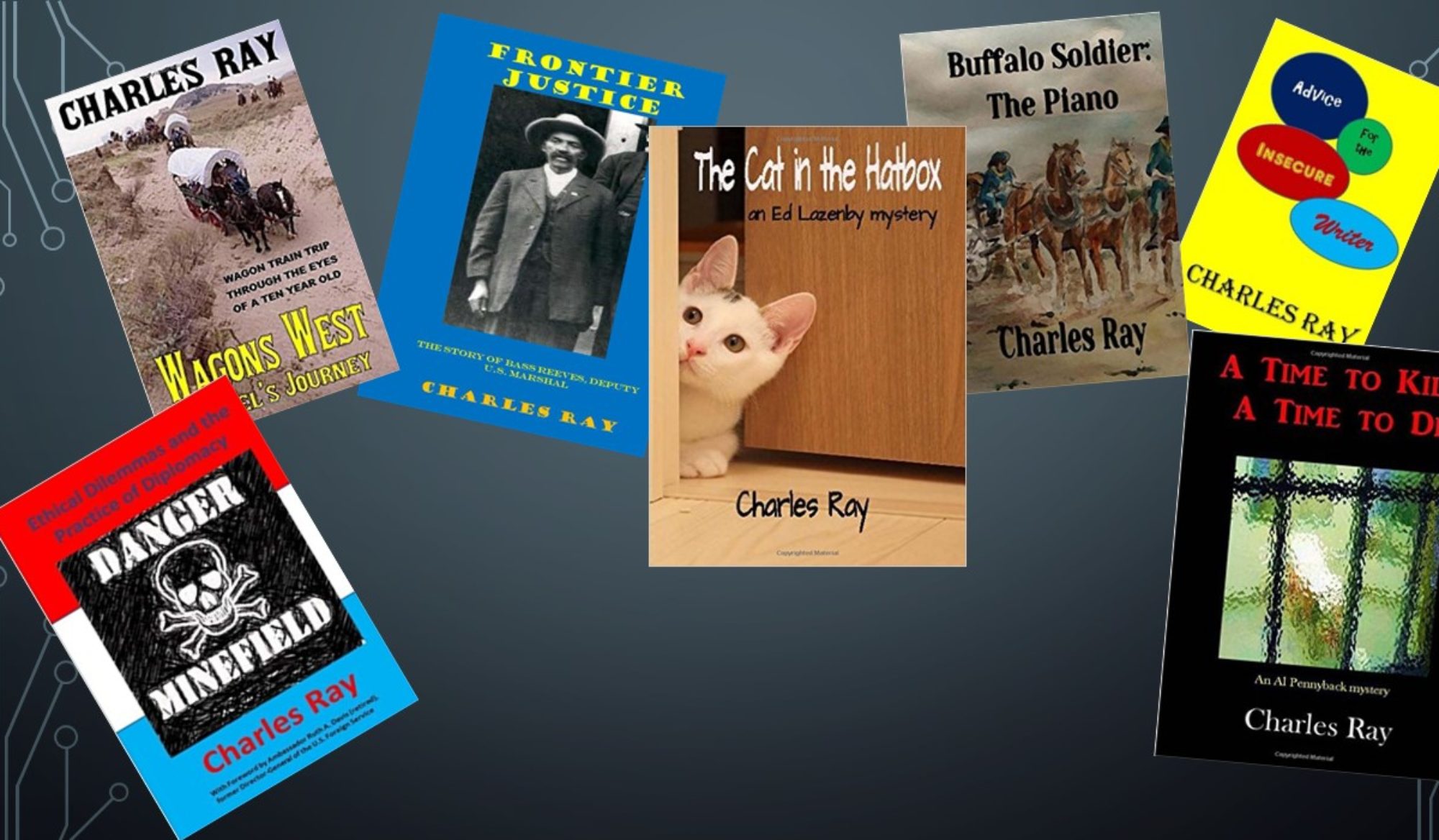

After a not-so amicable divorce from the ‘publisher’ who’d issued my first two books, and the decision to immerse myself in the waters of independent publishing (which entailed learning layout and design and a few other skills), I began to crank books out in earnest. I started with a mystery series featuring a retired army special ops guy working as a PI in Washington, DC, soon added a western series about the famed Buffalo Soldiers of the US Ninth Cavalry, while still doing blogging and a little copywriting and content generation on the side. To my surprise, while they didn’t make any bestseller lists, my books actually began to sell—be bought—and reviews indicated people were reading and responding to them. Sometimes those responses were negative, but I learned from those negative reviews, and I think the books got better. Hell, I know they got better; I went from selling two to three copies a month to fifty or more, and some months I even managed to sell as many as 800 copies of one of my e-book versions. I even have a couple of books that are what I call my perennial sellers. My book on Bass Reeves, the first African-American appointed a deputy US marshal west of the Mississippi, which has been out for three years now, averages 10 to 15 e-book and 4 to 10 paperback sales per month, even now. That’s nothing to brag about, but with more than 20 books doing that now, it is significant. Last year (2016) my net income from book royalties passed the $7,000 mark. That doesn’t put me in the Fortune 500, not even the Fortune 500,000, but for an indie author, that’s nothing to sneeze at.

After a not-so amicable divorce from the ‘publisher’ who’d issued my first two books, and the decision to immerse myself in the waters of independent publishing (which entailed learning layout and design and a few other skills), I began to crank books out in earnest. I started with a mystery series featuring a retired army special ops guy working as a PI in Washington, DC, soon added a western series about the famed Buffalo Soldiers of the US Ninth Cavalry, while still doing blogging and a little copywriting and content generation on the side. To my surprise, while they didn’t make any bestseller lists, my books actually began to sell—be bought—and reviews indicated people were reading and responding to them. Sometimes those responses were negative, but I learned from those negative reviews, and I think the books got better. Hell, I know they got better; I went from selling two to three copies a month to fifty or more, and some months I even managed to sell as many as 800 copies of one of my e-book versions. I even have a couple of books that are what I call my perennial sellers. My book on Bass Reeves, the first African-American appointed a deputy US marshal west of the Mississippi, which has been out for three years now, averages 10 to 15 e-book and 4 to 10 paperback sales per month, even now. That’s nothing to brag about, but with more than 20 books doing that now, it is significant. Last year (2016) my net income from book royalties passed the $7,000 mark. That doesn’t put me in the Fortune 500, not even the Fortune 500,000, but for an indie author, that’s nothing to sneeze at.

So, you might be asking, what the hell does all this have to do with schizophrenia or writing process? Okay, fair point. I guess I did digress a bit there. Now that I’m officially retired from government service and am the master of my own schedule, here’s my writing process.

I get up every morning between 5:00 and 7:00 AM, depending on how late I went to bed, and after showering and fixing my breakfast, I hit the keyboard. I write until 9:30 or 10:00, and then take a break. I watch a little morning TV—the oldies channels with series from the 60s and 70s—or go to my studio I’ve set up in my garage, and paint or take pictures. Then, after lunch, I hit the keyboard for another hour (1:00 to 2:00 PM). I take another break of an hour or so, and maybe work in the yard or paint some more. Supper for me is around 6:30 PM, and then I plan to be at the keyboard by 7:30 or 7:45, and I write until 10:00 or 11:00 PM. That’s every day, unless I have to go out for a consulting job, a speech, or to conduct the occasional workshop. When that happens, I take a notebook with me and write notes on the subway or plane, or in the hotel if it’s a long trip. One way or another I get that minimum of 2,000 words written each and every day.

It has become such a routine now, I don’t really even think about it. Hadn’t  thought about it, in fact, until my editor friend asked her question. But, that’s the answer to how I’ve done over 60 books in 11 years. The thing is, I wasn’t even counting them as I was cranking them out, and didn’t even notice it until a few years ago, a friend who was introducing me to speak at an event, mentioned that I’d writing a sh-tload of books. I still don’t stop to count them often, but every now and then, someone will mention it, and I’ll count. It keeps going up. I don’t have a target, maybe to have at least one book for each year of my life—no, I know, to have more than 100. That’s nice, round number, don’t you think.

thought about it, in fact, until my editor friend asked her question. But, that’s the answer to how I’ve done over 60 books in 11 years. The thing is, I wasn’t even counting them as I was cranking them out, and didn’t even notice it until a few years ago, a friend who was introducing me to speak at an event, mentioned that I’d writing a sh-tload of books. I still don’t stop to count them often, but every now and then, someone will mention it, and I’ll count. It keeps going up. I don’t have a target, maybe to have at least one book for each year of my life—no, I know, to have more than 100. That’s nice, round number, don’t you think.

Oh, and was I right? It’s schizophrenia, isn’t it?