When I’m reading

fiction, and I come to a passage of description where the author goes into

excruciating (to me) detail; describing every wrinkle in the fabric of a shirt,

or every knot hole in a tree; I skip it. If I encounter a second such passage,

I skip it. The third time, unless I’m reading the greatest story ever told

(and, I’m still waiting to encounter that story), I stop reading. Long,

overly-detailed passages of description, whether of character, setting, or . .

. well, just about anything, stop the flow of the story, and leave you

suspended in a kind of nether world outside the story, and for me, this is a

complete buzz kill. I suspect that’s so for most readers.

Because I don’t like

too much description, when I write, I try to avoid it as much as possible. This

is not to say that there is no description in my stories—a certain amount is

needed to set the scene for a reader. But, if you’re smart, you will allow the

reader to use his or her imagination to fill in the details, which, in turn,

pulls them deeper into the story.

Here’s an example. A

character enters a house late at night. You wish to show that danger lurks in

the shadows in every room. Following the principle of ‘show, not tell,’ you do

not say ‘danger lurks in every room,’ but nor should you go overboard in trying

to show that the character is entering a dangerous place. So, how, in a case

like this, do you engage the reader’s imagination?

Let’s try something

like this:

“The door made a soft moaning sound as he eased it open.

He stepped into the room, and the darkness seemed to reach out and grasp him by

the throat, and press against his chest. The dust in the air felt like spiders

crawling across his skin.”

Okay, let’s stop the

description right there, and have our character do something, preferable something that evokes a sense of impending

peril. If you like, you can insert short phrases later on to reinforce the

sense of danger, just to keep the reader on his or her toes. Get the point? Did

you get a few mental images of what lay ahead for this character? That’s how to

do it.

Same thing goes for

character descriptions. You don’t have to list every wart or wrinkle on a

character. Paint it in broad strokes and let the reader fill in the rest,

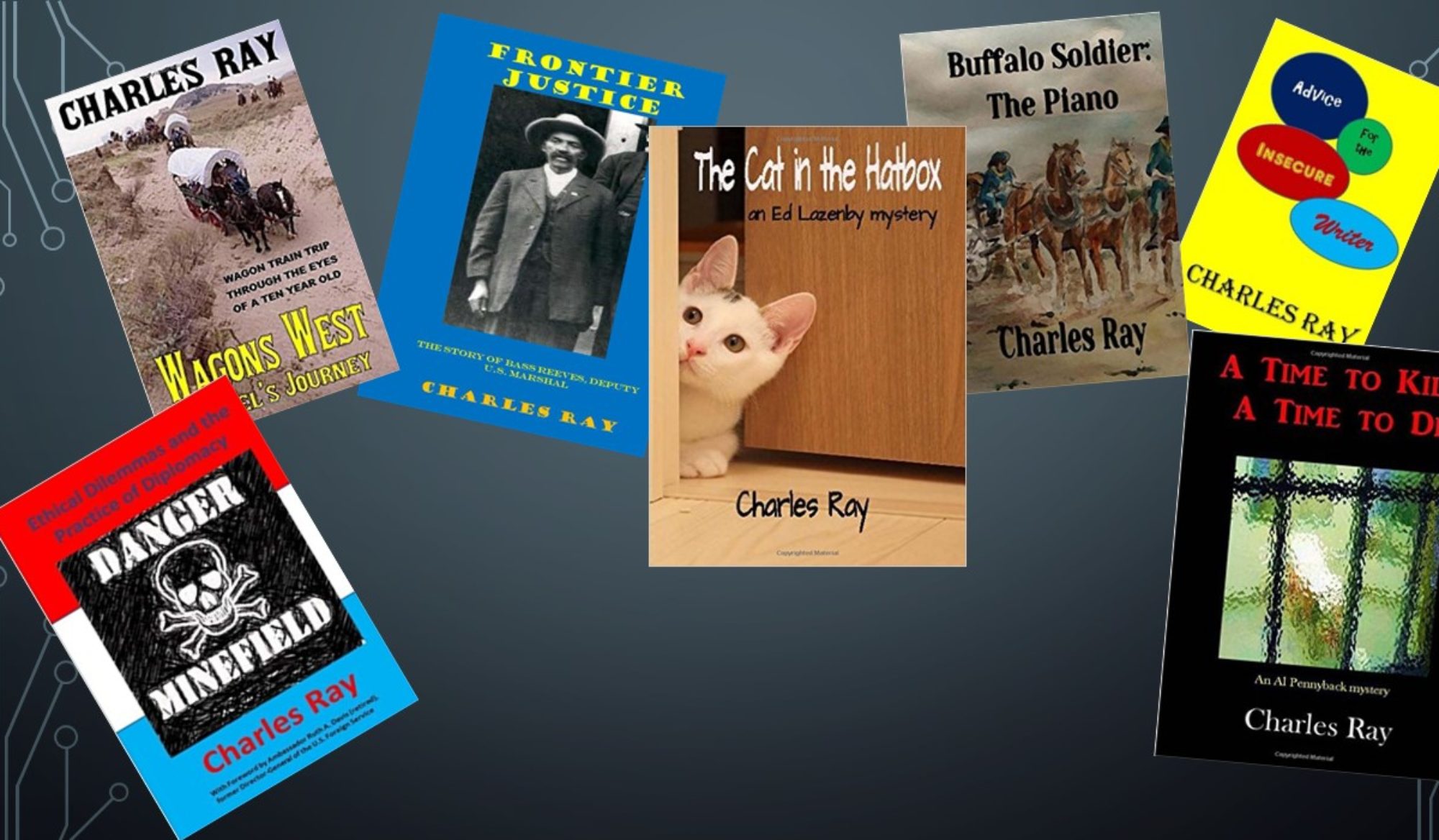

especially for supporting characters. I have a recurring character in my Al

Pennyback mysteries, for example; Mom, the proprietor of the hero’s favorite

restaurant. She’s known only as Mom, but some reader feedback tells me that

some people think they know her. Here’s how I described her in one book in the

series: “Mom sat at her usual place at

the end of the counter, near the cash register, looking out over her domain

like some ancient Ethiopian queen. She wore a bright yellow, one-piece dress

that, despite containing enough fabric to make a roomy two-man tent, barely

contained her girth.” Can you see Mom?

Bet you can.

That’s it for now. Keep

writing.

Like this:

Like Loading...