A little holiday-themed short story that I hope you will enjoy.

1.

Daxon Grump was angry. This was nothing new. He was always angry about something. But, on this occasion, he was angrier than he’d been in a long time. He didn’t like not getting his way, and the dunderheads—his word for them—in his parliament had committed the cardinal sin; they’d refused to give him something he’d wanted from the day he put on the crown of Washuptown.

Formerly the owner and star performer in the Grump Circus of the Stars, Daxon Grump had ascended the throne of Washuptown by happenstance and accident, but after a few days there had accepted it as his due. In other words, he’d become royal, regal, and kingly in all the ways those words are thought of as negative, alienating his parliament, and causing him to doubt the efficacy of a parliamentary monarchy, where he had to share power with a bunch of former tradesmen or royals who hadn’t been high enough in the bloodline to lay claim to the throne.

Because of this unfortunate situation—fortunate for him—the parliament had thrown the succession open to any citizen who could convince the people he was fit to lead. He, with his many years of experience parting suckers from their coin to see the acts in his circus, had campaigned throughout the kingdom of Washuptown, promising the world, and enthralling the crowds of peasants and merchants who had long labored under the often heavy and uncaring hands of the royals. In the end, he had prevailed. His victory against the other contenders had been narrow, but it was just enough to push him to the head of the list. That some of the votes for him had been purchased with the horde of gold he’d amassed over the years was something he gave little thought to, just hoping that it would never be known.

Two days after the coronation, he’d met with Michel Orwell, speaker of parliament, and one of the people who had seen the direction in which the wind of change was blowing and supported him early, and each time he recalled that meeting, his blood boiled, his nostrils flared, and he felt like throwing things.

“But, your majesty,” Orwell had said after he’d presented him with what he felt was a brilliant idea. “I think your desire to protect the kingdom from outsiders is admirable, but the method you propose to accomplish it is not within the ability of the royal treasury to achieve.”

“What?” He reacted in shock and anger, the same way he’d always done whenever one of his circus minions had had the temerity to disagree with one of his ideas. “How much could it cost to build a simple wall around the kingdom? All the gold the royal family amassed during King Odan’s reign has to be sufficient to do that.”

“Hardly, your majesty. We have . . . expenses and obligations that must be met. A wall would deplete the treasury to an extent that we would not be able to do so. Worse, Yuletime is fast approaching, and we must be able to pay the holiday bonuses. It is expected.”

Grump was furious. He was livid. Obligations my foot, he thought. We’re paying hundreds of scribes and counselors to sit around creating mountains of paper that never go anywhere, and that less than half the kingdom could read, and the other half couldn’t understand. And, there were the princely salaries each of the members of the parliament received each month.

This was unacceptable. He would find a way.

“Very well, Speaker Orwell,” he said in a tight voice. “You are dismissed. I will consider this, and when I’ve made a decision, I will get back to you.”

As the obese speaker, his loose jowls flapping bowed and backed out, Grump was having the beginnings of another brilliant idea.

2.

He thought about it for a full two days. Well, actually, he didn’t do much thinking, for he’d already made up his mind before he’d even dismissed that toady Orwell. Mostly, he sat around two days stewing and doodling on a loose sheet of foolscap. He’d waited for the dramatic effect. His years in the circus had taught him the importance of timing and pacing.

On the third day he was ready.

He had a page summon Orwell.

The fat fool came rushing in twenty minutes later, sweating like a peasant fresh in from the fields. He stopped in front of Grump and bowed deeply.

“You wished to see me, your majesty?”

“I do,” Grump said. “Did you get a chance to read the proposal I sent to your office yesterday?”

Orwell’s head bobbed up and down.

“I did, your majesty, and may I say it is an elegant design, elegant, while at the same time appearing quite sturdy.”

Grump didn’t smile, because, despite the toadying words, he sensed a ‘but’ in there somewhere. That ‘but’ wasn’t long in coming.

“But there is, your majesty, a problem, and I’m unable to get my fellow parliamentarians to agree to supporting it.”

“They refuse to support it,” Grump sputtered. “Do they not know that this is my signature project, that it will be my legacy?”

“Uh, they know all this, but the, ah, problem, you see, is that there is not enough in the treasury to pay for it.”

Grump smiled now, for he’d anticipated that objection.

“I have a plan for dealing with that little problem,” he said. “All we have to do is not pay all the useless hangers-on, like scribes and counselors for, oh, say six months, and there will be more than enough in the treasury to build my wall.”

Orwell, though, was an experienced bureaucrat and a savvy politician. He was not to be outdone.

“That will pay for the materials, sire, but what of the laborers who must build it? That will not be a small expense.”

Again, Grump smiled, which caused Orwell to shudder.

“Ah, the laborers,” Grump said. “I suppose we will have to pay for supervisors. I was thinking I could use the salary paid to you almost-useless parliamentarians for that. As for the common labor, I believe if I ask, enough citizens of Washuptown will volunteer their labor. After all, Washuptonians love me, do they not?”

Orwell knew that was a dangerous question to answer incorrectly, for he’d learned very early that Grump was a man who valued what others thought of him above all but increasing his wealth—as long as they thought well of him. On the other hand, he knew that the citizens looked forward to Yuletime, that week in the spring of each year when they paid homage to the Yule tree, the source of heat, building materials, perfume, tools, and many other necessary items in their daily lives. It was a time they exchanged gifts, planted new Yule trees, and held long parties at which a potent liquor made from the sap of the tree was consumed. What they would definitely not want to do would be spending many, many months constructing a wall around the kingdom which would complicate trade with neighboring kingdoms, and interfere with Yuletime festivities.

“Of course, the people love you, your majesty,” Orwell said. “But you must remember that Yuletime approaches, and the people might not like anything to interfere with observance of this sacred holiday. Oh, and that reminds me, there is one other expense that the treasury must provide for; each year the palace throws a huge Yuletime feast for the populace. It’s somewhat expensive, but well worth it in the goodwill it generates.

“Oh, did I now tell you, Orwell,” Grump said. “In order to ensure the health of the treasury, so that my wall can be adequately funded, I’ve decided to cancel Yuletime this year.”

Orwell’s eyes went wide. When Grump held up a royal edict written in his own crabby handwriting, that said, ‘Yooltime is cansuled until I get MY wall. Grump Res,’ followed by the royal seal of Washuptown, his blood ran cold.

This would not go over or down well with the citizens. Never in the history of the kingdom had the holiday been tampered with. He did not know how the people would react.

“Don’t you think that’s bit extreme, sire?”

“Of course not. My people love me. You’ll see. I’m having the population summoned this very afternoon in the forecourt of the palace, where I will announce my great plans. You and your parliamentarian colleagues will be there.”

Orwell shuddered and swallowed hard. He had no choice. He would have to be there, but he had a sinking feeling that bad things were about to happen.

Worse, he thought, the simpleton misspelled ‘Yuletime’ and ‘cancel.’ The people will forgive him the second, as most of them probably can’t spell it either, but as for the first . . . well, that was sacrilege. Oh yes, he thought, bad things are about to happen.

3

.

Just before the midday meal hour—not, in Orwell’s opinion a good time to assemble people to listen to a speech, even if the speech was for good news, which this one was not to be—most of Washuptown’s population had assembled in the castle’s forecourt. There were puzzled looks on many faces as people wondered why their new king wanted to speak with them. Some smiled, for they figured, if it was important enough for the king to call the whole kingdom together for it, it would be a great thing to participate in. Orwell and his fellow parliamentarians, though, were most definitely not happy to be there, for they knew that when the king announced his grand plan, there was no telling how the people might react—Orwell had shared Grump’s plan with the others, and it’s safe to say that each and every one of them was quaking in his boots.

After making the people wait for half an hour—Grump had read somewhere that this was a sign of royalty, and showed his importance—Grump appeared on the balcony, beaming down at the crowd and waving his hands. Somewhat nearsighted, he didn’t notice the frowns on some of the faces in the crowd. Not everyone was happy at being made to stand so long in the hot sun, and be force to miss the midday meal.

Grump waited until the murmuring, which he interpreted as murmuring of affection for his royal self, to die down, and then he held up his proclamation, and began explaining why he was doing it.

As those in the front rows read the proclamation, stopping on Yooltime, and being shocked and passing this bit of heresy on to those behind them, the murmuring took up again.

Thus, only the guards on the balcony heard the part about government workers not getting paid for six months. The sergeant of the guard sent one of the guards to carry that message through the castle.

Orwell’s colleagues gasped when they realized that parliamentarians’ salaries were included in the things Grump was not going to pay.

The crowd didn’t hear Grump’s call for free volunteer labor to build his wall. They were so steamed that the king butchered the name of their most sacred holiday, they’d stopped listening to his speech, and were talking among themselves.

It was only the rising volume of his voice that caught their attention.

“Citizens of Washuptown, what say you to my proposal?”

4.

There was a moment of stunned silence.

Then, from the middle of the crowd, someone shouted, “Off with his head!”

“No, no,” someone else shouted. “That’s too good for him. Let’s boil him alive.”

Grump could not believe at first what he was hearing. This couldn’t be happening. The people loved him, they would not be turning on him like this. Something was amiss. He turned and looked at Orwell.

“What are they saying, Orwell? Why are they not happy?”

The pudgy parliamentarian bowed, keeping his eyes averted from the confused king.

“They are angry, your majesty. I warned you that it would be a mistake to muck with Yuletime.”

“But they should be happy that I’m bringing security and safety to the kingdom. When I made speeches about it before I won the crown, they cheered wildly. Why have they changed?”

“Well, your majesty, it’s like this. They did not feel insecure until you started making speeches about it. They still do not really insecure. Washuptonians simply like good speeches, and you are adept at giving them what they like. Now, though, you have given them something they do not like, or rather, you are threatening to take something they like away from them. I fear that you have pushed them to anger, and I cannot say what they might do.”

“They’re threatening to boil me alive. They can’t do that to their king. They should love me.”

“Sire, they loved you when you were making speeches. If you had left it at that, they might’ve continued to love you. Now you are proposing to do things they do not like or want to do. If I might be so bold as to venture an opinion, I think they just might boil you alive.”

Grump’s ruddy complexion turned gray.

“No, that cannot be allowed.” He turned to the captain of the guard. “Captain, have your men drive these people away from here. Any who resist, throw them into the dungeons.”

The guard captain didn’t move.

“Captain, did you hear me?”

“Aye, your majesty. I heard you. But you just announced that royal employees are not being paid. We guards are royal employees. If we are not being paid, we cannot work. It’s in our contracts. We are not allowed to work for free.”

Grump looked confused. He turned to Orwell.

“Is that true?”

“Yes, your majesty. Employees such as guards have an iron-clad contract. No pay, no work.”

“Okay, okay, I’ll pay you from my personal funds. Now, move those people.”

“Uh, I’m afraid they are not allowed to accept pay other than from the royal treasury, your majesty,” Orwell said. “That is to ensure their loyalty.”

Grump had a sudden revelation. His own petard, his explosive idea that would bind everyone in the kingdom to him and have them bend to his will forever, was now affixed firmly to his nether regions. He had painted himself into a corner on a precipice, with no handholds, and was about to be pushed into the abyss. Being king was suddenly not such a glorious prospect. He wished he’d stayed in his circus.

“W-what am I to do, Orwell. I do not wish to be boiled, dead or alive.”

“Well, your majesty, there is one thing that you might consider. I cannot guarantee that it will work, but it just might placate them, and they just might spare you.”

To a man in a hole, a rope is preferred, but if a string is all that is dropped down, he will grasp it.

“Anything, Orwell, I’m willing to do anything to stay alive.”

“If you publicly relinquish the crown, and put the power in the hands of the parliament, temporarily, mind you, until we can select another to be king. I am confident that the people will be merciful.”

Grump thought about it for all of ten seconds. He’d wanted to be king, but most of all he just wanted to continue to be. Running a circus wasn’t all that bad. At least, he had total control over the clowns, acrobats, and other performers.

“Very well then, I resign effective immediately.”

“Repeat so the people hear, your majesty.”

Grump walked to the railing and leaned forward. “I, King Grump, do hereby relinquish the throne. I am no longer your king. Yuletime is still on.”

The murmuring stopped. People stared up at him.

“You really gonna quit?” some asked.

“Yes, I quit.”

Orwell stepped forward.

“The king has abdicated. The parliament is now in control, and Yuletime is not cancelled. Oh, and there will be no wall built, and all royal employees are to report to work immediately. Yuletime bonuses will be paid on the morrow.” He turned to the captain of the guard. “Captain, please escort Daxon Grump to the gate and see that he leaves the royal premises.” He then turned back to Grump and not so gently removed the crown from his head.

With a broad smile on face, the captain ordered two guards to seize the commoner. The two burly young men grabbed Grump by his arms and unceremoniously lifted him so that his toes dragged across the cobblestones. At the gate, they heaved him through the opening like a sack of waste and slammed the gate shut.

He picked himself up, dusted himself off, looked around to see if anyone had seen what had happened. Elated to see that his humiliation was unwitnessed by any but the perpetrators, he walked away, whistling.

5.

That should have been the end of it for Daxon Grump. Unfortunately, his stars were not so aligned. Some of the people he’d paid to vote for him were heard complaining in a local inn that the coins he’d used to pay them were iron, painted to look like gold sovereigns, and when they’d tried using them to buy things, they’d had them flung back in their faces and themselves flung from the establishments.

When word of this reached Orwell at the parliament, he and his colleagues conferred and came to the decision that such malfeasance could not go unpunished. An example had to be made so that in the upcoming elections the candidates would be motivated to campaign honestly.

A guard was dispatched to Grump’s circus, and he was again unceremoniously hosted between two guards, and thrown into an iron-barred cage and transported to the castle dungeon. The parliament held a speedy trial at which those who had received his counterfeit coins confessed that they’d sold their votes to one Daxon Grump. Each of them received a token two lashes on the back and warned never to commit such a grave offense again. Grump, found guilty of fraud and counterfeiting, was spared the lash. He was sentenced to ten years in the dungeon, allowed to leave his cell once a day only to clean the castle stables and pig sty.

No one would speak to him, and it was forbidden to utter his name. Only the pigs, grunting when he fed them scraps from the castle kitchen, not unlike the swill he received each morning and evening in his cell, seemed to call his name, uttering, ‘grump, grump’ continuously as the plunged their snouts into the gray, mushy mess he fed them.

Grump had always dreamed of a captive audience shouting his name over and over, and adoring him. He finally had realized his dream, and they were his to rule over for ten years.

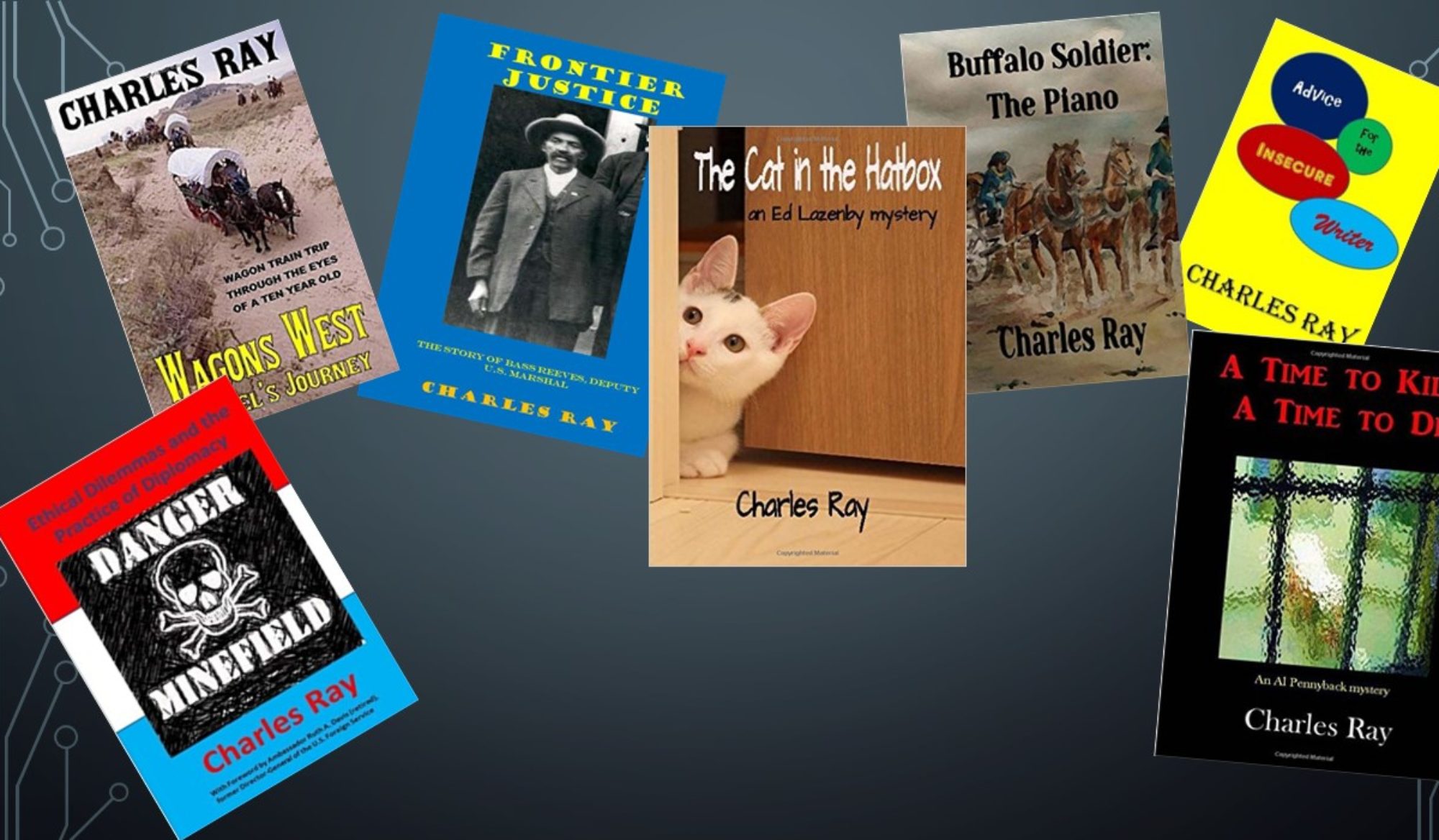

After a not-so amicable divorce from the ‘publisher’ who’d issued my first two books, and the decision to immerse myself in the waters of independent publishing (which entailed learning layout and design and a few other skills), I began to crank books out in earnest. I started with a mystery series featuring a retired army special ops guy working as a PI in Washington, DC, soon added a western series about the famed Buffalo Soldiers of the US Ninth Cavalry, while still doing blogging and a little copywriting and content generation on the side. To my surprise, while they didn’t make any bestseller lists, my books actually began to sell—be bought—and reviews indicated people were reading and responding to them. Sometimes those responses were negative, but I learned from those negative reviews, and I think the books got better. Hell, I know they got better; I went from selling two to three copies a month to fifty or more, and some months I even managed to sell as many as 800 copies of one of my e-book versions. I even have a couple of books that are what I call my perennial sellers. My book on Bass Reeves, the first African-American appointed a deputy US marshal west of the Mississippi, which has been out for three years now, averages 10 to 15 e-book and 4 to 10 paperback sales per month, even now. That’s nothing to brag about, but with more than 20 books doing that now, it is significant. Last year (2016) my net income from book royalties passed the $7,000 mark. That doesn’t put me in the Fortune 500, not even the Fortune 500,000, but for an indie author, that’s nothing to sneeze at.

After a not-so amicable divorce from the ‘publisher’ who’d issued my first two books, and the decision to immerse myself in the waters of independent publishing (which entailed learning layout and design and a few other skills), I began to crank books out in earnest. I started with a mystery series featuring a retired army special ops guy working as a PI in Washington, DC, soon added a western series about the famed Buffalo Soldiers of the US Ninth Cavalry, while still doing blogging and a little copywriting and content generation on the side. To my surprise, while they didn’t make any bestseller lists, my books actually began to sell—be bought—and reviews indicated people were reading and responding to them. Sometimes those responses were negative, but I learned from those negative reviews, and I think the books got better. Hell, I know they got better; I went from selling two to three copies a month to fifty or more, and some months I even managed to sell as many as 800 copies of one of my e-book versions. I even have a couple of books that are what I call my perennial sellers. My book on Bass Reeves, the first African-American appointed a deputy US marshal west of the Mississippi, which has been out for three years now, averages 10 to 15 e-book and 4 to 10 paperback sales per month, even now. That’s nothing to brag about, but with more than 20 books doing that now, it is significant. Last year (2016) my net income from book royalties passed the $7,000 mark. That doesn’t put me in the Fortune 500, not even the Fortune 500,000, but for an indie author, that’s nothing to sneeze at. thought about it, in fact, until my editor friend asked her question. But, that’s the answer to how I’ve done over 60 books in 11 years. The thing is, I wasn’t even counting them as I was cranking them out, and didn’t even notice it until a few years ago, a friend who was introducing me to speak at an event, mentioned that I’d writing a sh-tload of books. I still don’t stop to count them often, but every now and then, someone will mention it, and I’ll count. It keeps going up. I don’t have a target, maybe to have at least one book for each year of my life—no, I know, to have more than 100. That’s nice, round number, don’t you think.

thought about it, in fact, until my editor friend asked her question. But, that’s the answer to how I’ve done over 60 books in 11 years. The thing is, I wasn’t even counting them as I was cranking them out, and didn’t even notice it until a few years ago, a friend who was introducing me to speak at an event, mentioned that I’d writing a sh-tload of books. I still don’t stop to count them often, but every now and then, someone will mention it, and I’ll count. It keeps going up. I don’t have a target, maybe to have at least one book for each year of my life—no, I know, to have more than 100. That’s nice, round number, don’t you think.