I’m all for eliminating bias, gender, religious, or ethnic, for our language.

Assuming, for instance, that the pronoun ‘he’ represents both, or all, genders is not only sexist, but it’s illogical. Even though the number of men and women on the planet is almost equal, albeit there are imbalances in some regions (There are, for example, far more women than men in the former Soviet states, and in Asia, the Arab world, and Northern Africa, men outnumber women), in general women outlive men globally. So, if we want to be fair, the common pronoun to refer to all people would be ‘she.’ Of course, we know that life has never been fair.

The war over use of gender-neutral language has been going on for decades, and I’m a total supporter—with a few exceptions.

Some of the made-up words being used make writing sound a bit silly and trivial, to me at least, and they often complicate writing, making it almost incomprehensible. I won’t even go into words like ‘ze,’ ‘hir,’ or ‘s/he,’ or the salacious ‘s/he/it.’ I would, though, like to address one of my pet peeves; the often indiscriminate use of ‘they,’ ‘their,’ or ‘them’ as a singular gender-neutral pronoun.

Now, I acknowledge that this usage has been more or less common practice since the 1800s, and in many cases is correct, and not really a problem. But, when used indiscriminately, they can be quite confusing—and, sometimes sound silly. Take, for instance, the sentence, ‘John put their new address on their Facebook page,’ or ‘The baby threw their bottle at me.’ In the first sentence, upon whose page did John put whose new address? In this case, it’s probably safe to assume John is male, so the use of ‘his,’ doesn’t strike me as biased in any way, and it’s much easier to understand the meaning. In the second, we’re clearly talking about a single baby, and although we don’t know the gender, couldn’t we just write, “The baby threw the bottle at me’? Doesn’t that communicate the same meaning?

The problem with universal use of these words as a substitute for gender-specific pronouns is that if you’re not careful it can lead to miscommunication. Allow me to give you a brief example:

‘The college president released their policy on academic freedom today. They stressed that they want students to be able to express their opinion without fear that they will punish them. They can be assured that they will zealously guard their rights under the US Constitution and the bylaws of their institution.”

I could go on, but I hope I’ve made my point. Is it clear who ‘they’ and ‘their’ are referring to in this passage? Imagine, if you will, if this went on for a thousand more words. I don’t know about you, but I would be completely befuddled.

Maybe I’m a traditionalist, or a coward, or just lazy; or, as some of the students in my professional writing workshop no doubt think; I’m an old codger resisting the inexorable and inevitable transformation of the English language to reflect changes in social consciousness. Actually, I like to think of myself as a practical person who believes that the objective of writing is to clearly communicate a message to an audience. To that end, my approach to the issue of gender neutrality is to eschew blatant and obvious gender-biased language. Policemen become law enforcement officers, and I don’t add ‘-ess’ or ‘ette’ to words to indicate femininity. A waitress is a server, and a stewardess is a flight attendant. I also don’t refer to ‘male nurses,’ or ‘female doctors,’ and a poet is a poet regardless of gender. This applies to my fiction as well as my professional nonfiction writing. If necessary, I’ll rewrite a sentence, eliminating the pronouns if there is no other way. For example, instead of writing, “I took my grandson to the zoo so they could learn about species conservation,’ I’ll write, ‘In order to impart information about species conservation, I took my grandson to the zoo.’

In my professional writing workshop, for Rangel Foreign Affairs Scholars, I have to deal with 15 college seniors each summer, and this is a constant debate. While I appreciate and applaud their commitment to gender equality, my main goal is to help them learn to communicate accurately and effectively in a government setting. I’m careful to emphasize that I understand and support their point of view, and don’t expect or want them to change it. But, at the same time, I urge them to remember why they’re taking the workshop; their goal should be learning how to write effectively and communicate accurately. They are there to learn how to convey an often complex message to a diverse audience. I want them to continue to strive for equality, but to do it without mangling or muddying their message.

I have this depressing feeling sometimes that I’m fighting a losing battle. But, you know what; I will never stop trying.

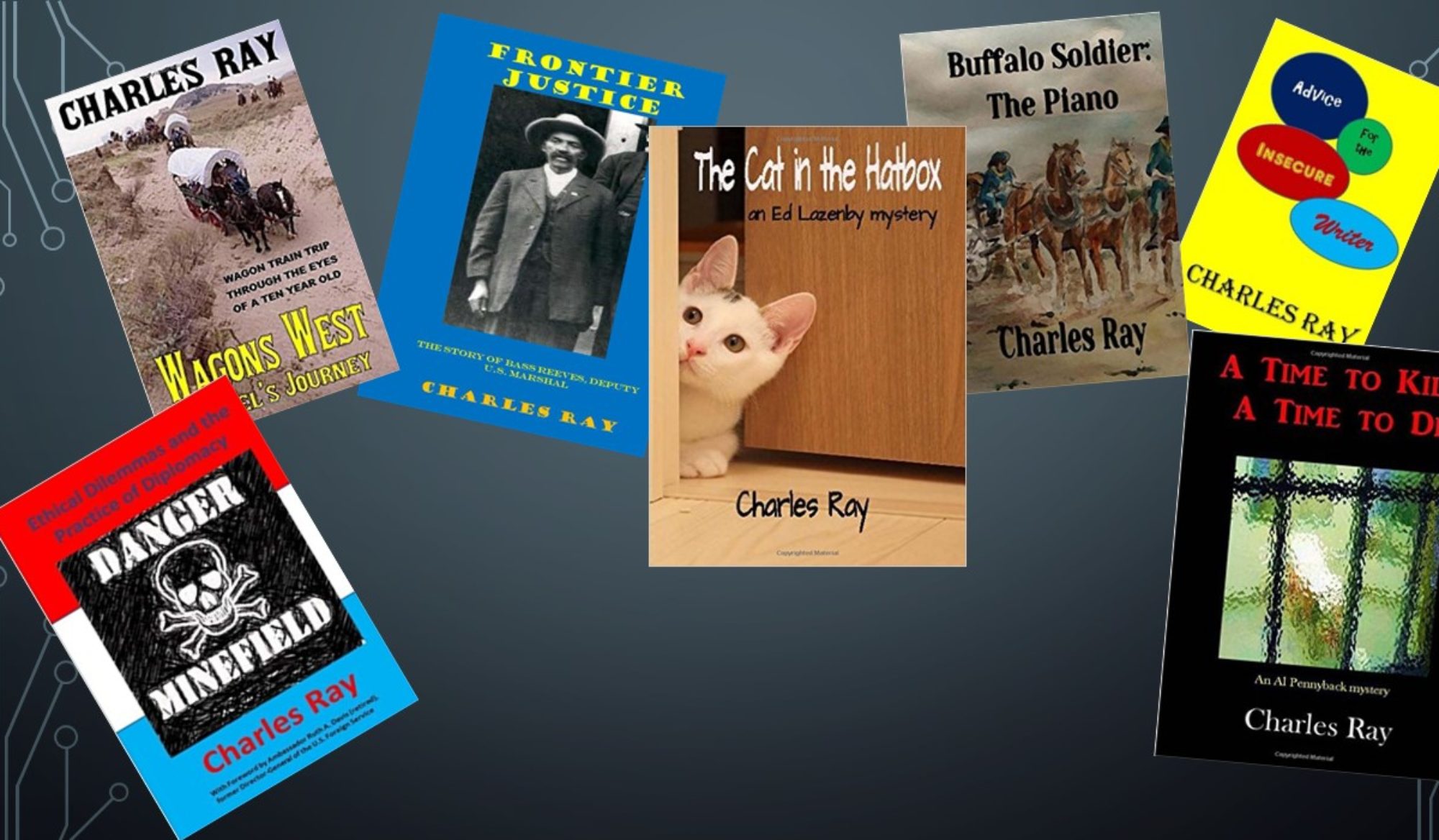

After a not-so amicable divorce from the ‘publisher’ who’d issued my first two books, and the decision to immerse myself in the waters of independent publishing (which entailed learning layout and design and a few other skills), I began to crank books out in earnest. I started with a mystery series featuring a retired army special ops guy working as a PI in Washington, DC, soon added a western series about the famed Buffalo Soldiers of the US Ninth Cavalry, while still doing blogging and a little copywriting and content generation on the side. To my surprise, while they didn’t make any bestseller lists, my books actually began to sell—be bought—and reviews indicated people were reading and responding to them. Sometimes those responses were negative, but I learned from those negative reviews, and I think the books got better. Hell, I know they got better; I went from selling two to three copies a month to fifty or more, and some months I even managed to sell as many as 800 copies of one of my e-book versions. I even have a couple of books that are what I call my perennial sellers. My book on Bass Reeves, the first African-American appointed a deputy US marshal west of the Mississippi, which has been out for three years now, averages 10 to 15 e-book and 4 to 10 paperback sales per month, even now. That’s nothing to brag about, but with more than 20 books doing that now, it is significant. Last year (2016) my net income from book royalties passed the $7,000 mark. That doesn’t put me in the Fortune 500, not even the Fortune 500,000, but for an indie author, that’s nothing to sneeze at.

After a not-so amicable divorce from the ‘publisher’ who’d issued my first two books, and the decision to immerse myself in the waters of independent publishing (which entailed learning layout and design and a few other skills), I began to crank books out in earnest. I started with a mystery series featuring a retired army special ops guy working as a PI in Washington, DC, soon added a western series about the famed Buffalo Soldiers of the US Ninth Cavalry, while still doing blogging and a little copywriting and content generation on the side. To my surprise, while they didn’t make any bestseller lists, my books actually began to sell—be bought—and reviews indicated people were reading and responding to them. Sometimes those responses were negative, but I learned from those negative reviews, and I think the books got better. Hell, I know they got better; I went from selling two to three copies a month to fifty or more, and some months I even managed to sell as many as 800 copies of one of my e-book versions. I even have a couple of books that are what I call my perennial sellers. My book on Bass Reeves, the first African-American appointed a deputy US marshal west of the Mississippi, which has been out for three years now, averages 10 to 15 e-book and 4 to 10 paperback sales per month, even now. That’s nothing to brag about, but with more than 20 books doing that now, it is significant. Last year (2016) my net income from book royalties passed the $7,000 mark. That doesn’t put me in the Fortune 500, not even the Fortune 500,000, but for an indie author, that’s nothing to sneeze at. thought about it, in fact, until my editor friend asked her question. But, that’s the answer to how I’ve done over 60 books in 11 years. The thing is, I wasn’t even counting them as I was cranking them out, and didn’t even notice it until a few years ago, a friend who was introducing me to speak at an event, mentioned that I’d writing a sh-tload of books. I still don’t stop to count them often, but every now and then, someone will mention it, and I’ll count. It keeps going up. I don’t have a target, maybe to have at least one book for each year of my life—no, I know, to have more than 100. That’s nice, round number, don’t you think.

thought about it, in fact, until my editor friend asked her question. But, that’s the answer to how I’ve done over 60 books in 11 years. The thing is, I wasn’t even counting them as I was cranking them out, and didn’t even notice it until a few years ago, a friend who was introducing me to speak at an event, mentioned that I’d writing a sh-tload of books. I still don’t stop to count them often, but every now and then, someone will mention it, and I’ll count. It keeps going up. I don’t have a target, maybe to have at least one book for each year of my life—no, I know, to have more than 100. That’s nice, round number, don’t you think.